Contributed by K. L. Marshall

“Faith and Oil” tells the story of conservative Christianity’s relationship with America’s oil industry. It shows how the libertarian values of big oil companies, such as government deregulation of business practices and curbing laws that protect the environment, became embedded within the theologies of the Religious Right. These theologies of oil later found their being in the public consciousness through the rise of Sarah Palin and led to the election of Donald Trump.

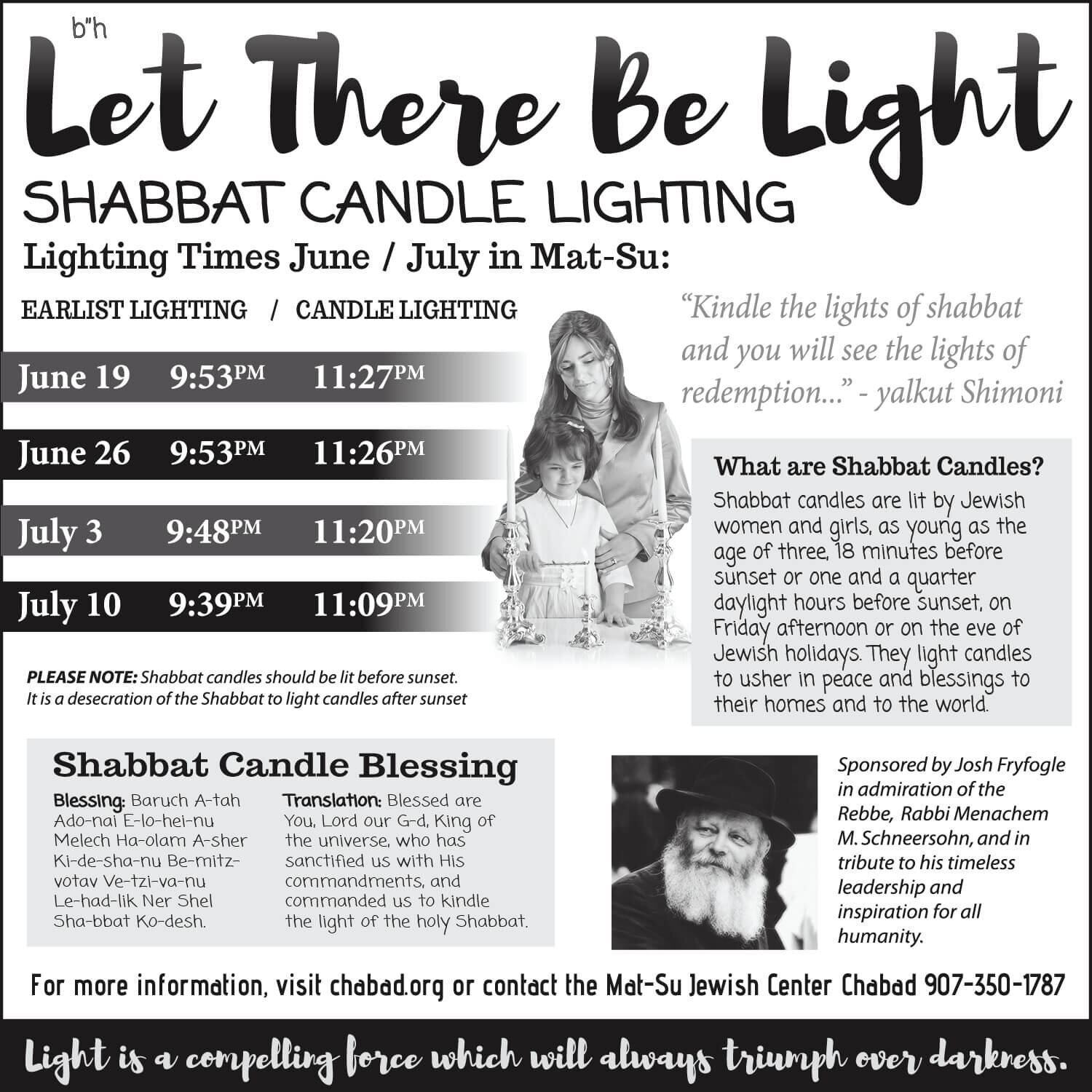

When Katie Couric interviewed Sarah Palin during the 2008 presidential campaign, the Alaskan governorturned-vice-presidential candidate said, “Alaska is a microcosm for the world.” While Palin may not have been referring to the state’s diversity, two years later, in 2010, the US Census named the Anchorage neighborhood of Mountain View as the most diverse neighborhood in the entire country. Three of the city’s high schools are the three most diverse in the United States, and every other Anchorage public school ranks in the top one percent. In other words, by some measures, Alaska’s largest city is more diverse than New York City, Chicago, Houston, and Los Angeles. Travel about 35 miles north of Anchorage, to Sarah Palin’s hometown of Wasilla and the broader Mat-Su Valley, and the sight is vastly different. Small fundamentalist churches dot the landscape, and upwards of 20% of children are homeschooled by their parents. Wasilla represents the ideal of “Middle America,” the rural and suburban heartland where small-town politics uphold family values and a capitalist work ethic. Middle America stands for the family farm, the small business, and a Jeffersonian vision of democracy; to many, it also stands for homogeneity and the proverbial WASP—the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant. Though diversity in the Mat-Su Valley is increasing, Wasilla remains one of the least diverse cities in the country. In some ways, life in the Mat-Su Valley seems to be a reaction against the modern, diverse center of Anchorage. Nothing in the state of Alaska is unaffected by its oil industry, which helps fuel the engine of modern America. Alaska’s oil fields brought jobs and an influx of cash, and with it, Alaska Natives entered the cash economy and immigrants traveled to the state looking for work. Oil money flooded the state’s coffers when an 800-mile pipeline was completed in 1977. Many people, resisting the modernization of Alaska, retreated into fundamentalist enclaves while themselves enjoying the benefits of the state’s oil-based wealth. Within a 35-mile stretch of Alaska, one can find the epitome of modernity and a fundamentalist reaction against it, both created by an economy and culture built around the extraction of oil. Alaska truly is a microcosm for the world. Nobody in the state has been more affected by its oil industry than the Alaska Natives, who have seen their lands polluted by oil and their millennia-old ways of life eroded. Many Alaska Natives have left their subsistence lifestyles and reshaped their cultures within the cash-based oil economy; efforts to increase drilling in the interior of Alaska promise to bring more money to the Native peoples, while Natives who resist drilling insist that they cannot eat oil or the money that it brings. The challenges that they have faced represent the challenges of indigenous peoples throughout the world who are struggling to hold onto their ways of life in the face of globalization and the continued growth of oil. While working on this book, I was confronted with another way that Alaska is a microcosm of the world. During the 2008 election season, an arsonist set Wasilla Bible Church, where Sarah Palin attended with her family, on fire with worshippers gathered inside. This hate crime committed against conservative Christians in Wasilla is just one in a growing number of hate crimes being committed against Muslims, Jews, LGBTQ+ communities, immigrants, minorities, and other groups all across the world.

K. L. Marshall is a PhD candidate at the University of Edinburgh School of Divinity. Her research focuses on the relationship between fundamentalist religion and nationalism.